France Bans Nigerian students, others From Bringing Family

France has passed a new immigration law that makes it harder for migrants to bring their families and access social benefits, sparking criticism from both the left and the right.

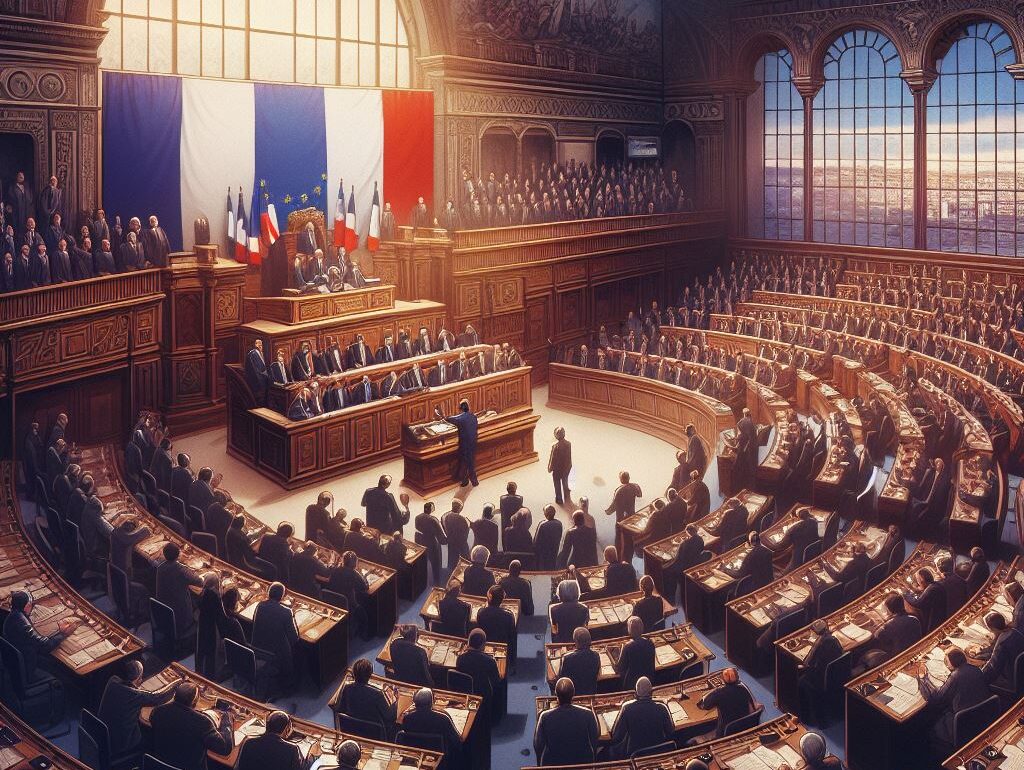

The law, which was approved by the parliament on Monday, was supported by President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist Renaissance party and Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally (RN).

However, the law also caused a rift within Mr Macron’s party, leading to the resignation of Health Minister Aurélien Rousseau, who opposed the bill. Several other MPs from the ruling party also voted against or abstained from the bill.

The law also faced resistance from some regional authorities, who said they would not implement some of its measures, especially the one that limits the access of non-citizens to welfare benefits.

The law was revised after a previous version was rejected by the parliament last week, when both the RN and the left-wing parties voted against it. The government then made some changes to the bill, making it more restrictive.

The new law bans the detention of minors in immigration centres and introduces a quota system for legal immigration. It also extends the waiting period for migrants to access social benefits from three months to six months.

One of the most controversial aspects of the law is that it creates a distinction between citizens and migrants, even those who are legally residing in the country, in terms of eligibility for benefits.

The law was welcomed by the right-wing parties, who praised it as a victory for their agenda. Ms Le Pen said the law was an “ideological victory” for the far-right, while Eric Ciotti, the leader of the Republican party, called it “firm and courageous”.

The left-wing parties, on the other hand, accused Mr Macron of pandering to the far-right and betraying his own values. Olivier Faure, the leader of the Socialist party, said: “History will remember those who betrayed their convictions.”

The law was passed just hours before the European Union announced a new pact on asylum and migration, which aims to reform the bloc’s asylum system and address the challenges posed by the influx of migrants.

The pact, which was agreed by the EU governments and the European Parliament, includes the creation of border screening centres and the faster return of rejected asylum seekers. It also introduces a solidarity mechanism that allows the relocation of asylum seekers from the countries of first entry to other member states.

The pact still needs to be formally approved by the Parliament and the member states.

The new French law exposed the divisions within Mr Macron’s party, which lost its majority in the parliament in the elections in June 2022. Since then, the government has struggled to pass its legislative agenda, often relying on the support of the right-wing parties.

The prime minister acknowledged that some of the provisions of the law might not be in line with the constitution and said that the government would seek the opinion of the Constitutional Council, the highest judicial authority in the country.

The law was also condemned by human rights groups, who said it was the most regressive immigration law in decades and that it violated the principles of equality and dignity.